Encouraged by climate change, episodes of drought are on the increase in France and worldwide. Between high tech innovation and older methods, farmers are finding ways to adapt to water shortages.

1976, 1989, 2003, 2020, 2022... A list of good vintages? Alas, no. These summers of intense agricultural drought (or 'edaphic drought' if you want to impress at Scrabble) have left their mark on several generations of French farmers. And everything points to 2023 becoming one of them, with the attendant increased water restrictions for private and professional consumers alike.

As a quick recap, drought (although there are several types) means that the soil lacks water for plants, directly affecting their production and indirectly that of animals. This is caused by a combination of factors whose magnitude increases as climate change gains momentum: a lack of precipitation, high temperatures promoting evaporation, the condition of the soil (available water capacity, absorption capacity, porosity), and wind.

A range of solutions

Drought impacts the irrigation needs and yields of the agricultural sector, and thus prices (and tastes!) for the end consumer. Although there is no magic wand, there are complementary solutions. One is the storage of water – although this could create tensions depending on the size of the project. Others are clearly more consensus-forming, such as connected technology. Here, sensors accurately measure the crops’ water needs, enabling the farmer to use their smartphone to access the data in real time, adjust irrigation, and avoid wastage.

Another solution is to adapt the crops to the changing climate. In the face of recurrent droughts, an increasing number of farmers are replacing their sweetcorn crops (very water-intensive in summer) with sorghum, a grain used in India and sub-Saharan Africa that is much better at resisting heatwaves.

In Noirmoutier, the chips are certainly not down

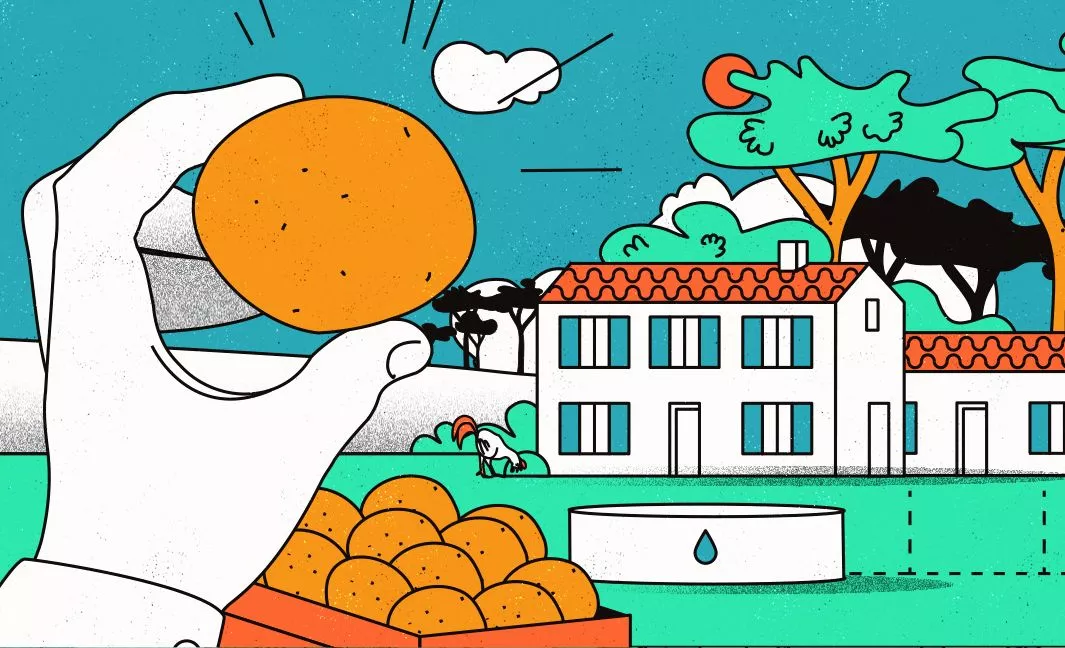

To save water, some French local authorities use a time-honed method, which could inspire the rest of the country. One example is the island of Noirmoutier, located in the Vendée region and considered a jewel of the Atlantic coast. Although fewer than 10,000 people spend the winter there, the population increases ten-fold in summer.

Forty years ago, the island found a way to cultivate its tasty potatoes, of which it produces 12,000 tonnes each year. It irrigates the crops with reclaimed wastewater, saving huge amounts of water. Noirmoutier does not have its own water table for drinking water – this is conveyed from a reservoir on the mainland. Two treatment plants recycle the inhabitants’ wastewater from sinks, showers and toilets which, once treated, irrigates the crops via liaisons between fields and storage basins built in the 1980s. To avoid all risk of contamination, the water is analysed each week.

Thanks to this ingenuity, the Noirmoutier potato has developed to the point of being regularly considered one of the world’s tastiest varieties. While this example illustrates the benefits of technology in fighting drought, the ancestral tools have not uttered their last word. In France as in elsewhere in Europe, particularly Spain’s Extremadura region, irrigation channels used in the Middle Ages have been brought back into service. More than 1000 years after their creation, they still work perfectly!